- Home

- Bruce Geddes

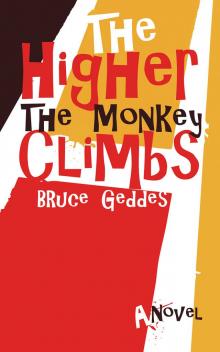

The Higher the Monkey Climbs

The Higher the Monkey Climbs Read online

THe

HigHer

THe MoNKey

CLiMbs

THe

HigHer

THe MoNKey

CLiMbs

A Novel

BRUce Geddes

Copyright © 2018 by Bruce Geddes

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

Publisher’s note: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Geddes, Bruce, 1969–, author

The higher the monkey climbs / Bruce Geddes.

ISBN 9781988098579 (EPUB)

ISBN 9781988098586 (mobi)

I. Title.

PS8613.E33H54 2018 C813’.6 C2018–900455–X

Printed and bound in Canada on 100% recycled paper.

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Now Or Never Publishing

901, 163 Street

Surrey, British Columbia

Canada V4A 9T8

nonpublishing.com

Fighting Words.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the British Columbia Arts Council for our publishing program.

For Gena

A personality has its own ways.

A mind might observe them without approval.

~ Saul Bellow, Herzog

1

This is a story about my cousin Tony Langlois, who, when it was all over, turned out to be one of the few good people I have known. He is dead now and though the memories are often painful to recall (on the last night I saw him alive, for instance, he knocked me cold with a single punch) I still feel that I owe him. A debt of gratitude, you might call it. A settling of outstanding accounts. Obviously, I will never be able to properly repay him. Tony has been dead for over a year now. Then again, what could be so wrong in trying? He was a good man and the people in his life didn’t always understand this.

All of this began late in the winter of 2009. At the time, I was into the final, difficult months as an associate at a medium-sized legal concern in Toronto, a downtown firm specializing in immigration. Neither especially lucrative nor very exciting, it is an area of the law one settles for rather than pursues out of school. Anyway, things weren’t going especially well for me there. For example: On the day I received that first strange message from Tony, I had just come from court where I’d expected to defend a client against a deportation order. Except the client, wanted in his native El Salvador for the murder of a priest, failed to appear. This was bad. Bad for him (for he was declared a fugitive) and bad for me, for nothing plays worse with a judge than a lawyer who can’t convince his client to show up for court.

I should have been furious with my client or pleaded with the scowling judge for a new date, but by that time in my career I no longer had any real expectations of my professional self. As I walked through the fluorescent-lit courthouse halls, threading one arm then the other through the puffy tubes of my winter coat, I felt nothing, neither anger nor shame. Despite long-ago, earnest aspirations to something greater, as a lawyer I had never achieved much more than a kind of passable mediocrity. There were no higher court appearances, no precedents set, no giant fees collected. Nothing in the papers worth clipping and keeping in a desk drawer for my descendants to discover and marvel at after my death.

Instead, at mid-career, the peak for most people, I was struggling to stay interested. That swell of pride and power I once felt when I entered a courtroom? The little lift that came when I thought I might be making a difference in someone’s life? Gone, all of it. We take our soul’s fuel from many sources and, while I can’t say exactly when or how it happened, the fact remained that I no longer needed to win justice for my clients nor even to hold the government to its own sets of rules. Instead, at forty-four years old, (too young to give up, probably) I now focused my efforts more and more on a far more modest ambition: making sure nothing went wrong for me.

But even still. I hadn’t thought things were so bad that my clients would prefer to test their luck on the lamb rather than trust me to argue their case.

With the Salvadorian now officially a fugitive, I left the grey-stone court buildings, pushed through the gates, and merged onto a crowded sidewalk. The wind whipped at my wool trousers below my coat and chunks of road salt crunched under my shoe soles. I clenched my face and tucked my chin into the pocket of warm scarf and made for the nearest PATH entrance, aiming to complete the trek to my office in subterranean comfort. Once underground, I pulled out my phone and dialled the voicemail, hoping my client had called to explain his absence. But there was only one message. From my cousin Tony.

It took me a long moment to recognize his voice. Noises interfered in the background, furniture legs scraping, a faint buzz and crackle.

“Tricky?” he began. “I hope you’re doing okay. It’s, uh, Tuesday morning, just after ten.” He spoke slowly. His voice sounded sleepy and stressed. “Anyways, I got myself into a situation here in Wanstead and I was wondering, well, what I need is a lawyer and I could really use some help. I don’t even know if you’re still doing that, but I guess you are. Anyways, I’m ah . . . I’m in jail actually, so let me know if you can help out, okay? I hope you’re doing okay, I hope your family’s good.”

There was a pause. Shouting in the background.

“It’s Tony. Tony Langlois.”

It was nice that he called me Tricky, a nickname I first adopted in high school, a play on my last name (McKitrick) and some kind of backhanded allusion to the disgraced Nixon. I thought it was very clever then. (Still do, kind of.) We were once close, my cousin and I, almost brother-like. But we lived in different cities now and saw each other less and less often. In fact, after a string of never fulfilled promises to get together, we had stopped trying and it had been many years since we’d seen each other. We did keep in touch through email, but rather than real, thoughtful paragraphs describing the teeters and totters of the accumulating years, our brief exchanges consisted mostly of forwarded photographs of oversized hamburgers or vegetables that had grown into the shape of genitalia. Check this out! was about as much as either of us had bothered to write in some time. And though there had never been an incident—a disagreement or dispute—to provoke our distance, I still felt awkward hearing from Tony like this, in a context normally reserved for more intimate, more trusting relationships.

I paused near a bank of screens updating stock prices and five-year bond yields and listened to the message again, searching for familiar qualities in Tony’s voice and wondering what he could have done to get himself arrested and tossed in jail.

I thought: He must have slugged someone.

When Tony and I walked into our first year at Richmond C.I. together in our canvas high-tops and black t-shirts from concerts we hadn’t been allowed to attend, he brought with him a growing reputation for fighting. Wanstead is a scrappier city than most; dispute resolution usually involved threats and fists and in those fall months of grade nine, when turfs are established and reputations cemented, Tony was always willing to fight and always won and soon the other tough kids knew to avoid him. Even our teachers began to notice and his grades crept cautiously higher, from barely passing to barely respectable levels.

Then, in the early

months of the tenth grade, he suddenly developed a rigid stance against fighting.

“My father didn’t raise a bully,” he declared.

To most of his friends, it seemed like Tony had lost his nut. Or maybe he’d finally met his match; maybe this sudden pacifism had been imposed by someone bigger and stronger and even crazier for violence. Slouched against walls of green locker doors, they speculated on the fight and the opponent, figuring he came from another school, possibly from the States where “those guys fight to kill.”

But I knew better. I knew that this fresh policy and the slogan tagged to it was something he’d picked up from my father Gord at one of their breakfast sessions. Those meetings began after Tony beat up a bully named John Latouf and John’s parents called the police. Because it was Wanstead, nothing came of it—no more than some finger wagging and stern warnings—but after that fight, Gord, who was fifteen years older than Tony’s long-absent father, started taking him for breakfast to Betty’s, an unhappy little diner across the street from the UCF, where Gord worked as the union’s legal counsel. Over twice-weekly omelettes and stacks of pancakes, they would sit at Gord’s usual table in quiet conference, Gord asking questions, Tony answering, Gord commenting, inserting gentle advice that Tony always took, even as he struggled to understand.

In the beginning, I resented these sessions, feeling that my territory was being encroached upon. But then something strange happened: Tony’s attitude toward me began to change. What had been a loose friendship based on a few common ancestors was now tinged with something just a little like reverence. As though I were worthy of his admiration for the simple fact of being Gord’s son.

And that was something I could more easily absorb.

And so I mostly ignored their breakfast ritual, never asked what they talked about, and only ever heard about the tiny aphorisms Gord imparted when Tony uttered something like, My father didn’t raise a bully.

“But you never knew your father,” I pointed out.

It didn’t matter. “Anyone can beat people up,” he said. “It takes a man to know when it’s wrong and when it’s right.”

Instead of schoolyard scraps, Tony’s searching violence found its outlet in the boxing ring, where ropes and rulebooks and hovering referees offered the illusion of a controlled environment. He worked hard in the gym, trained several times a week and watched other boxers to learn. When his turns came up, he did very well, defeating all of his opponents, most of them without working very hard.

I remember those fights and watching Tony’s blond hair flop as he bounced and shuffled from rope to rope, the sound of his shoes on the canvas like fine sandpaper polishing wood, the way he read the other boxer with his narrow stare, as a general might study a map, looking for the right place to strike and fall back, strike and fall back. I remember the comments from other, more knowledgeable spectators about the size of his back muscles and the speed and power of his jab and I remember the gasps when his opponent opened himself up and Tony landed one.

But of course, standing knock-outs and three-minute rounds could never replace the thrill of street fighting and more than that, the easy certainty that justice was merely a question of being tougher than the guy whose face you were punching in. Boxing was good for Tony, it saved him from a lot of trouble. But I have often thought that it also robbed him—not unjustly—of something essential.

It all came apart on a Friday night in October, 1983. The bout was important for Tony. Members of the provincial boxing commission had come down with an eye to putting him on a list of aspirants who would be fast-tracked for the Olympic team. They sat in folding chairs in the front row, each of their impassive faces showing one credential or another—a misshapen nose on one, a scar across another’s eyebrows, a third with shrivelled beans for ears. His opponent was a guy named Danny Dillon, an older, slower, weaker, flat-footed boxer from a club in the county. We’d seen him in the parking lot coming in, puffing an Export A for courage.

After introductions, the referee had them touch gloves and the fight began. In a pair of red satin trunks, bought new for the fight and designed to demonstrate his patriotism (should there even be any doubt) Tony was handling him easily, landing hard jabs, a solid hook. Dillon missed with his punches and grew frustrated as he couldn’t even tie Tony up to regroup. Those of us who knew him smiled as he toyed with his opponent, slowing down the pace before landing a thrilling combination for which the hapless Dillon had neither defense nor response.

The bell rang to end the second round and Tony spun towards his corner, nodding to the people he knew in the crowd. Behind him, his face red with humiliation and early signs of bruising, Dillon swung and landed a shot on the back of Tony’s head, just below the padding of the head gear. We rose to our feet, outraged, protesting. The referee stepped in, waving his arms in the air, shouting disqualification. But Tony, who to that point had barely been touched by Dillon’s gloves, simply lost himself. All the lessons about restraint and honour? They dissolved into the steamy gym air as he chased Dillon into a corner, catching him and beating him mightily, full wind-up punches to the head and body. At first, I cheered his blows, but then Dillon fell heavily to the canvas, shielding his head with his arms. Tony spit out his mouthpiece and kept swinging and landing, each punch coming with a sickening ‘pffst’ when the air from his glove escaped.

My father stood beside me. “No! Tony. Don’t!”

But everyone in that tight little worked-up crowd was either shouting or gasping and Tony heard nothing. It’s strange how we go to these spectacles with the desire to see furious action, to see one man destroy another with his strength and speed. All the sweetly scientific talk about defensive stances and punching accuracy and footwork—it’s like praising a painting for its frame. No one ever stands to cheer a defensive stance. Defeating the other man—the more decisively the better—is the main thing, the only thing. And yet, victory has to come within the rules of the game. That same violence outside the rules? Well, a person feels a bit uncertain and vulnerable and it gets to be too much to stomach. And so, when both corners emptied and Tony went after Dillon’s trainer, and then Dillon’s brother, and then the referee, and finally his own trainer (who escaped by diving through the ropes into the row where the Olympic guys were sitting) pretty much everyone in that gym was feeling sick.

At a special meeting the following day, the boxing commission made the swift decision to ban Tony from the ring for life. With the temperament he displayed, they said, how could they risk having him on the team? Devastated, he came to my father. Gord agreed to speak to the Chair, confident that Tony would be re-instated.

“You think he’ll listen?” Tony asked.

We were seated in the living room of our house on Aberdeen Street, a place reserved for guests or Christmas or formal meetings like this one. My father was still dressed in his grey workday suit, his tie removed, the white shirt collar opened two buttons. His hair, greyer every year, was trimmed short, as it always had been, even during the seventies. He was enthroned in his usual seat, a low-slung, high-backed, black-leather armchair set in the most distant corner, next to the fireplace. Only one light was turned on, a towering table lamp behind Gord that cast his shadow well past the middle of the room.

I sat on one end of the sofa, Tony on the other. With his hair combed flat, his socks matching for once, he wore a narrow black tie over a tight, short-sleeved golf shirt and sat straight on the cushion’s edge, hands folded tensely on his lap, head cocked in my father’s direction as though to make sure that each of Gord’s syllables registered.

“If he knows what’s good for him, he’ll listen,” I said.

“You,” Gord said, pointing at me. “You stay out of it.” And then, to Tony, “We’ve done business together before. I think I can work something out with him. Get me a formal letter of apology by Friday.”

“Apology!” I said, my torso lunging forward, though n

ever losing contact with the seat cushions. “You know it was Dillon who crossed the line. You were there!”

But Tony didn’t want my help. He looked at me straight, shook his head, and made a slashing gesture with his flattened hand. “I’m going to do what your dad says, here.”

“Be nice about it, understand, Tony?” Gord said. “You don’t know what got into you. You feel just terrible about it. You hurt your club. You hurt the sport of boxing, the sport you love and hope to be a part of for years to come. No, make it this:” He paused, took off his glasses, pinched his nose. “‘The sport you hope to practice at the highest level for many years to come.’ They’ll feel for your ambition. Also be sure to include this: ‘Nothing like that outburst has ever happened before . . .’ and—this should finish the paragraph—you promise, you sincerely promise that ‘it will never happen again.’ Close with an offer to attend aggression counselling. They’d never hold you to it—it’s boxing for Christ’s sake—but it will show how serious you are.” Gord returned his glasses to his face. “Make sure the handwriting is neat. No spelling mistakes. Get the grammar right. Richard will check it for you.”

“I can’t believe you’re making Tony apologize,” I said.

Gord crunched a pretzel in his molars, sipped from a tumbler of copper-red Special Old and ice. He glared at me, the same kind of languid glare—part disapproving, part disappointed—I still see in a judge’s face when things go wrong for me in the courtroom. He was in his mid-fifties and relaxed with his drink and his padded chair but sometimes I felt like all of that composure could break at any moment and sometimes, I think now, I pushed him hoping it would. The way characters in horror movies are compelled to open the precise door where trouble awaits. But of course with Gord, that coolness never did break and I was robbed of seeing what awaited me in the basement.

“There’s a lesson in this for you, too,” he said to me. “About who holds the cards and how things work. You could shut the hell up and listen for once.”

The Higher the Monkey Climbs

The Higher the Monkey Climbs